My introductory post for a Sci-Fi (and Fantasy) series is now up at The Leather Library (UPDATE: no longer exists). Whenever a post goes up there, I’ll post here as well to let you know.

I originally thought it would be like this:

But it’s not. Not yet, at least.

So far Dune and Solaris are on the queue. Right now I’m reading Anathem, which seems to have a lot of negative reviews, but it’s looking like you won’t see that from me. I’m really eager to get to this one. I’d like to work out some of the language in it and I hope to gain some insights from those of you who have read it or are planning on reading it. But I won’t say too much here.

I started with a classic, and so far they seem to be getting better and better. Thank you all for your recommendations…I’m enjoying the reading immensely.

UPDATE 2022: Since the original post was originally published on a site that no longer exists, I’ve decided to include the recently-found content from that post, which could possibly be merely a draft, here.

Desert and Ocean: Nature Personified

Dune (Frank Herbert, 1965) and Solaris (Stanislaw Lem, 1961)

I’ve decided to take on both novels at once, even though I was tempted to give each its own post. So this will turn out to be longer than I intended. However, the desert/ocean contrast was too intriguing to forego, and as it turns out, I just happened to read these—the first Sci-Fi novels of the series—in this order. Could it be destiny?

Super quick synopses, but slower than the speed of light:

Oh, yes, and SPOILER ALERT.

DUNE: Paul Atreides is the Lawrence of Arabia-like protagonist, a Bene Gesserit Bene Gesserit trained teenager (Sisterhood school of cool mind powers. As a male, Paul is not supposed to received this training, but his mother broke the rules in so many ways). His prophetic visions increase as he leads a group of Fremen to their victory over the evil House Harkonnen. (Fremen=These are humans whose eyes have turned completely blue due to their regular diet of spice, a drug that comes only from Dune. I, a Tucsonan, would call them Sci-Fi desert rats. They are militant but ecologically-conscious. They teach Paul how to navigate the land and make use of it for survival.) Harkonnen wishes to control the planet, Arrakis/Dune, to spend its most sought-after resource, a drug called “spice.” His narrow plans to obtain spice will thwart any efforts to create a livable planet rich with water, its most-needed resource.

Paul became the Freman’s religious leader with awareness of his victory to come. He’s also aware of his power of manipulation and has no qualms about bending the existing religious traditions to suit him. Oddly, he hardly doubts his powers of prophecy. For him they are taken for granted, but present an obstacle. He foresees a bloody war of which he is the instigator, but he cannot accept this. He also yearns for a normal life, a quiet domesticity with his love, but he knows this cannot happen, because he is destined to become great. He fights the visions, but at each seeming avoidance of fate, he brings himself further into it. The novel leaves us on a victorious note, but victory is in this case a foreboding ending.

SOLARIS: Psychologist Kris Kelvin hovers in a space station above the planet, Solaris, in an attempt to get some understanding of a conscious ocean covering the planet of two suns, two gravitational pulls. A love from his past comes alive—and yes, her body is really alive, she’s not a mere hallucination—as do colorful figures from the memories his colleagues. At first they attempt to rid themselves of these painful reminders of the past and their own failings, but soon they realize that the ocean is speaking to them through these quasi-apparitions, even if they can’t understand what’s being said. These figures act as mirrors. They aren’t quite the real person they represent, and they aren’t altogether different either.

Failure to make contact with the ocean leads one researcher on the team to suggest bombarding the ocean with radiation, which we know cannot be good.

Eventually, the researchers are told to come back to earth and abandon the project, which is becoming too much of a financial burden with little to show for it. But, as one character, Snow, says:

“It might be worth our while to stay. We’re unlikely to learn anything about it, but about ourselves…”

In the end, they abandon the station having failed to make contact with the ocean. Yet the last scene describes a particularly poignant moment in which the ocean seems to take interest in Kris. This is only a moment, however, and as he says, “…it bore my weight without noticing me any more than it would notice a speck of dust.”

I would like to come back to this scene, because there’s more to it than this. It’s one of the most fascinating scenes I’ve ever read.

Nature Personified

DUNE: In both novels we’re dealing with nature as a force so powerful it takes on the role of a character. The planet of Dune is deadly in so many ways. It’s a stark desert, a virtual wasteland…except for a few mysterious riches. It’s desolation is indicated in the native Fremen’s ultimate sign of respect—spitting. Special water-recycling suits are required if you live here, so a mouthful of saliva is a precious gift, a life force. The water of dead bodies is recycled too, but what would seem like a gruesome act is instead turned into a religious ritual.

The planet shows signs of greater things. Ecologist Liet-Kynes is on his way to discovering how to transform Dune into a more hospitable one, one rich in both water and spice. But making this transformation will require a long time and will take many lives, including his own. What’s needed is a new vision for the future, and someone who knows how to make use of what’s available. Unfortunately, he dies. Fortunately, there are others like him, though not many.

Then there are the worms. Giant worms. Fast giant worms that detect the slightest motion and will eat you, your spacecraft, and anything it can in minutes. To avoid the worm’s detection you must step quietly on the land. (Yes, that’s an apt metaphor). The worms represent a deadly force of nature, but when you climb on board one—if you can do it without getting yourself killed—you can ride it across vast distances and into safe territory. They also provide the spice which is necessary for life and space travel. To take advantage of nature and reap its benefits, you must understand it, you must see to its needs.

Similarly, Paul’s visions are a force, the force of destiny, and he is nothing but an actor in a grand scheme. His visions take him into danger, but perhaps fate has greater things in store for the planet of Dune. Perhaps if he rides fate instead of fighting it (which is futile anyway) he will find his sacrifice benefits the planet, which will in turn save all civilization. I’m just speculating here; I haven’t read the other books in the series.

On the other hand, Paul’s manipulation of religion to suit his ends could be a foreshadowing of disaster to come. If the goal of this series is to educate, the message could very well be that there is danger in this blind following of religious leaders. What better way to show this than end the series in a spectacular cacophony of destruction?

SOLARIS: In Solaris we have nature-as-character again, but here it’s more literal since the ocean is a living, conscious being. Its shining surface calls to mind a mirror, it’s depths the mystery of the subconscious. The ocean is of course the opposite of a desert, yet it too has dangerous powers—it takes the lives of many researchers who either go crazy and fly their spacecrafts into it, or it takes them if they fly too low. Hovering far above it is fairly safe, if you can stand the disturbing visits from your subconscious, but plunging into it’s greater mysteries means death.

The ocean remains conspicuously untouchable. Any attempt at communication with the ocean turns into an infuriating communication with oneself.

A lover from Kris Kelvin’s past had committed suicide due to his inability to understand her. In fact, his leaving behind the means by which she committed suicide suggests that he secretly knew and wanted this outcome. The semi-apparition version of this lover scares him at first, but she turns out to be his ideal woman, and he falls hopelessly and madly in love with her in a way he never has before.

Yet whom is he falling in love with? The semi-apparition’s lack of autonomy is made clear in that she can’t leave his presence or else she’ll die, only to be renewed the next day. This figure is none other than a product of Kelvin’s mind, manifesting itself in physical form thanks to the ocean’s powers. Kelvin’s greater love for the semi-apparition as opposed to the real woman reveals to him that love is really love of oneself. The greater the failure to make contact with reality, the greater the love. Love turns out to be a sick joke. Finis vitae sed non amoris—the end of life, but not of love, is a lie.

The problem of other minds is brought to the fore: How do we make contact with each other? Do we really? Or are we merely in communication with ideas of each other, never the reality? And if we never really make contact, what is love but a chimera?

In the final scene Kris acknowledges his defeat, he plans to return to earth. But before departing, he flies a spacecraft down to the ocean for the first time and lands on an island—once again, an apt metaphor. He reaches out to touch a wave, and the following occurs:

“…the wave hesitated, recoiled, then enveloped my hand without touching it, so that a thin covering of ‘air’ separated my glove inside a cavity which had been fluid a moment previously, and now had a fleshy consistency…I stood up, so as to raise my hand still higher, and the gelatinous substance stretched like a top, but did not break. The main body of the wave remained motionless on the shore, surrounding my feet without touching them, like some strange beast patiently waiting for the experiment to finish. A flower had grown out of the ocean, and its calyx was moulded to my fingers. I stepped back. The stem trembled, stirred uncertainly and fell back into the wave, which gathered it and receded…

I repeated the game several times, until—as the first experimenter had observed—a wave arrived which avoided me indifferently, as if bored with a too familiar sensation…Although I had read numerous accounts of it, none of them had prepared me for the experience as I lived it, and I felt somehow changed.”

The ‘glove’ the ocean creates suggests that, though we never make contact, we must persist in trying. When Kris resigns himself to this painful circularity of Other as self-reflection, he then makes himself available, he opens himself, insofar as that is possible. He learns that “the time of cruel miracles was not past.” He has faith, despite what he knows is possible, that he will continue to seek this distant contact, this illusion, this “cruel miracle,” whatever its worth.

So what if love is love of an idea? So what if we never make contact with reality? Doesn’t it affect us just as powerfully? As Snow points out in the first quotation, we might want to stick around to learn something about ourselves. Though love may not last, we are nonetheless changed by the experience.

Have you read these? How would you compare them? What did you think of the different focuses, Dune as sweeping in scope, Solaris as psychological?

I just finished re-reading the classic, Ringworld, and have gotten started on the sequel, The Ringworld Engineers. (My blog post from Jan 3 it about it.)

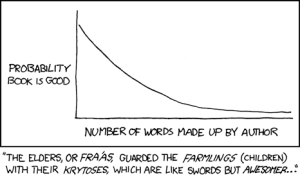

The thing about made-up words, as with most writing techniques, is that it depends on the skill of the author. In A Clockwork Orange (1962) author Anthony Burgess created a fascinating lingo for his characters. It adds greatly to the book’s tone and character. (Tip: ignore the glossary at the back and just stay in the flow of the narrative.)

Some authors have a background in linguistics that they bring into their books. Tolkien is a good example of that, and his invented languages are well-grounded and make a wonderful addition to his books.

Other authors just make up terms for things (as suggested in the (xkcd?) cartoon you have), and to me that’s more a distraction than a plus.

LikeLike

I totally agree about the use of language. It’s something I plan to talk about a lot, especially since I’m looking at these books from a writer’s POV and trying to learn something about technique. I tend to like it more when the words are grounded by a linguistic understanding. Etymology is quite revealing and all those layers of meaning can add a richness to the narrative that you just don’t get when you make up something out of the blue that relates to nothing.

xkcd, yep:

http://xkcd.com/483/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Greatest web comic ever! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well that’s my graph too and I’m sticking to it. I suffer a pathological aversion to all things mythical, in the nature of fantasy, and so forth, and have enough trouble sorting this reality out.

LikeLike

I hear you on having trouble sorting out this reality. So far I’m enjoying these books, but that could be because they were cherry picked by my insightful readers.

LikeLike

Wyrd Smythe is so right about Anthony Burgess. One of the best books ever, but he was an exceptional talent. Writing sf and fantasy demands a knowledge of linguistics so that the names and new words seem convincing. When it is done right, it affords a pleasure akin to poetry, from the sheer fun of the sounds and how they fit the things they name. Tolkien was of course the master at that! “Dune” is an all time favorite of mine, a wonderful mix of religion, ecology, economics and politics. “Solaris” is good, as is the film, though you have to be patient and not expect much of a plot 🙂

LikeLike

I totally agree with you—there’s a kind of poetry to the new languages, sometimes a play on the sounds of words or on their other meanings.

Oddly, I like Solaris more than Dune. I know I’m not supposed to say that, but something about it grabbed me. I watched the older Solaris film and found it infuriating…they messed with the arrangement of scenes and ruined the beautiful tension SL had created. I still haven’t seen the newer one, but I except it to be better, if only for the fact that newer movies tend to be better at keeping the action going. (Or maybe I’m just easily distracted.) 🙂

The best part of Solaris for me was the voice of the protagonist. It was easy to follow him into long scholarly digressions because there was always something at stake for him, and he somewhat distanced himself from the whole affair so that the digressions were colored with a kind of concealed hopelessness. I still can’t figure out how he did this, but it’s brilliant.

And the descriptions of the ocean were insane. I was filled with admiration at this accomplishment. I felt fully drawn into this bizarre world in near perfect clarity, as if I could see it. And I noticed the movie seemed to replicate these details very well, as if they were reading my mind. I give full credit to the author for his precision with detail. It was quite remarkable.

But yes, Dune was excellent too. I just felt Stanislaw Lem was a better writer.

You’re right about the plot in Solaris. It hadn’t quite occurred to me that there’s not much. It’s so psychological, and the plot is more internal than external. Thanks for pointing that out. I may have to use that in my write up!

LikeLike

The Left Hand of Darkness too is a brilliantly imagined other world and psychology!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy sitting right here next to me. I might have to check out Left Hand of Darkness too…it seems pretty popular.

LikeLike

I would say Lem is a more literary writer, where Herbert is more a genre writer. One is more about artistry and the other is more about storytelling. Our culture gives more weight to “serious” themes and verbal artistry than it does to storytelling, so that the former qualities add up to a “better” writer. Maybe that is justified, but I like it best when the two coincide. As in “A Clockwork Orange”!

LikeLike

You know, I haven’t read Clockwork Orange. It’s necessary, though, at some point in my life. God there are so many books I need to read!

I agree about combining storytelling and serious themes. I think it’s possible to have both. I tend to go for more traditional storytelling rather than verbal artistry, but those themes are pretty important to me. (Confession: I actually enjoyed Jonathan Franzen’s “Corrections” for his verbal artistry. I felt the story lacked meaning and purpose, but boy did he take me for a ride. If only it had more focus…he’s very talented.)

Lem did have some long digressions, but I didn’t mind them because I was so caught up in the voice. I really enjoy getting deeply in a character’s mind, but I felt like this was missing a bit from Dune. I also liked the tightness of Lem’s metaphors and imagery. The more I thought about them, the more I got out of them. It felt more complex and detailed, but Herbert had some interesting themes in Dune as well. I started working on my write ups of both last night and I decided to combine the two in one post. I liked the desert/ocean contrast; hopefully these will play out in an interesting way.

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to reading your Dune review!

LikeLiked by 1 person